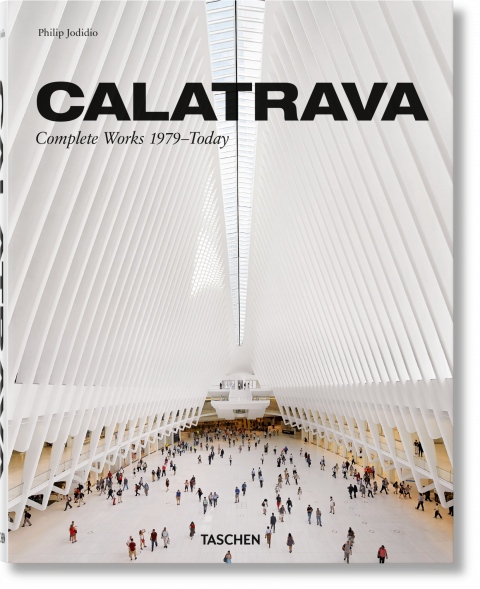

Art / Art Calendar / Environment, 1. November 2022

Artist Talk - HA Schult und Christa Steinle - Wir können die Gedanken der Menschen beeinflussen,

aber nicht ihr Tun.

HA Schult am 18. November beim Circular Valley in Wuppertal.

Alethea Magazine hat die Ehre, einen Artist-Talk wiederzugeben, den HA Schult mit der österreichischen Kunsthistorikerin und damaligen Direktorin des Grazer Joanneum Museums, Dr. Christa Steinle am 7.10.2006 im Palais Herberstein führte.

English version of the artist talk below.

HA Schult - Haus der Geschichte der BundesrepublikDeutschland ©HA Schult

HA Schult in Matera, 2019 ©HA Schult

Düsseldorf, 1. November 2022: Der deutsche Künstler HA Schult ist ein Visionär und erschafft Kunst des großen Augenblicks. Für ihn ist die Epoche, in der die Menschheit lebt, die Müllzeit und dies bestimmt sein Gesamtwerk. Vor über 33 Jahren erkannte er, welche Rolle Kunst bei der Lösung der Umweltprobleme spielen muss und schuf aus Müll eine Armee aus 2000 Skulpturen, weltweit bekannt als Trash People. 1996 war die Geburtsstätte der Trash People im römischen Amphitheater von Xanten und 1999 Auftakt ihrer bis heute 26-jährigen Wanderschaft um die Erde. Sie tauchen immer an ganz spezifischen Plätzen in der Welt auf, wie 1999 auf La Défense, Paris und noch im selben Jahr auf dem Roten Platz, Moskau, 2001 auf der Chinesischen Mauer, 2002 vor den Giza Pyramiden in Kairo, 2007 auf dem Plaza Real, Barcelona, 2011 auf Longyearbyen, Spitzbergen; die gesamte Reiseroute finden Sie weiter unten. Paris - Moscow - Beijing, war der Auftakt zur bisher größten Kunstaktion unserer Zeit.

Die Armee ist nach wie vor unterwegs; ein letzter großer Auftritt war in Sassi di Matera am 24. und 25. August 2019, in Anwesenheit des früheren Bundespräsidenten Christian Wulff, bevor Corona einige Aktionen erschwerte.

Nun sind die Trash People wieder auf Reisen. Eine aktuelle Gelegenheit, HA Schult gemeinsam mit seinen Trash People zu begegnen, ist am 18. November 2022 in Wuppertal beim Treffen des Circular Valley Forum (circular-valley.org)

Im Folgenden hat Alethea Magazine die Ehre, einen Artist-Talk wiederzugeben, den HA Schult mit der österreichischen Kunsthistorikerin und damaligen Direktorin des Grazer Joanneum Museums, Dr. Christa Steinle am 7.October 2006 im Palais Herberstein führte. Anlass war die Beteiligung des Künstlers an der von Peter Weibel kuratierten Ausstellung SLUM in der Neuen Galerie Graz am Landesmuseum Joanneum.

Die Aktionen waren schon immer aufsehenerregend: 1976 füllte HA Schult den Markusplatz von Venedig, von ihm als Salon Europas bezeichnet, mit einer Flut von Papiermüll. 1977, als Beitrag zur Documenta 6, ließ er ein mit Symbolen des Konsums beklebtes Flugzeug erst über der Skyline von New York fliegen, um es dann abstürzen zu lassen.

Im Interview erfährt man auch Hintergründe über die Trash People.

Trash People Golden Edition, Gorleben ©HA Schult

Reiseroute der Trash People:

1999: La Défense, Paris

1999: Roter Platz, Moskau

2001: Chinesische Mauer

2002: Giza Pyramiden, Kairo

2002: Stellisee, Zermatt

2003: Gorleben

2004: Grand Place, Brüssel

2005: Palais Herberstein

2006: Dom, Köln

2006: Piazza del Popolo, Rom

2007: Plaza Real, Barcelona

2007: Longyearbyen, Svalbard

2011: Telgte

2011: Schloss Mochental

2013: Poble del Mar, Barcelona

2013: Recycling Hill, Ariel Sharon Park, Tel Aviv

2014: Clairefontaine People, Luxembourg

2015: Tollwood People, München

2016: AQ Andreas Quartier, Düsseldorf

2016: Preußen Goes Europe, Berlin

2017: Werderscher Markt, Berlin

2018: Convent of Saint Agostino, Matera

2022: Circular Valley, Wuppertal

Christa Steinle: Schönen guten Abend, meine sehr geehrten Damen und Herren. Der Beitrag zur langen Nacht der Museen ist die Präsentation des Künstlers HA Schult, dem wir diese Installation im Hof verdanken, und wir sitzen gleichzeitig hier auch schon vor einem Werk aus der Sammlung der Neuen Galerie, nämlich Gizeh, Kairo von 2002, und ich möchte mich gleich vorweg recht herzlich bedanken beim Künstler dieser Arbeit,1000 Müllmänner, Trash People, Slum People, vor den Pyramiden in Ägypten. Ich würde sagen, wir steigen auch gleich ein mit diesen Müllmännern, bevor wir einen Rückblick auf die lange künstlerische Laufbahn von HA Schult machen, der ja eine ganz klassische Ausbildung an der Düsseldorfer Akademie hatte, aber sich von dieser Ausbildung extrem weg bewegt hat, so wie sich die Skulptur und die Malerei ja auch sehr stark verändert haben im Laufe bzw. zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts. Neue Formen der Kunst entstanden, Aktionskunst, Installationskunst – und das sind schon Begriffe, in deren Nähe sich dieser Künstler bewegt. Ich denke, Aktionskunst ist das auf jeden Fall, und mit diesen Müllmänner reisen Sie nun seit 10 Jahren durch die Welt. Es sind immer sehr spezifische Plätze, an denen wir diese Trash People vorfinden, sei es vor den Pyramiden in Kairo, sei es die chinesische Mauer, demnächst der Piazza del Popolo in Rom, aber sie waren auch am Roten Platz von Moskau; es sind sehr berühmte Plätze und man erreicht dadurch ein großes Publikum und ist in den Medien. Glauben Sie, ist das die neue Form der Kunst, dass man das größte Publikum erreicht, indem man sich von den Institutionen löst und in die Öffentlichkeit geht?

HA Schult: Nein, das ist keine neue Kunst, in der ich mich bewege, es gibt keine neue Kunst. Seit der Eiszeit ist es immer wieder dasselbe: der Mensch bäumt sich auf, um auf sich aufmerksam zu machen, durch ihn fließt das Leben, und so wie die Menschen in der Eiszeit in den Höhlen von Altamira vor den ersten Felszeichnungen getanzt haben, so tanzen sie heute in New York, in den U-Bahn-Waggons oder vor den Flächen der U-Bahn-Waggons. Sie haben ihre Botschaft oft her- ausgeschrien, aus den Ghettos in die anderen Stadtteile hinein, mit Hilfe der Kunst. Die Kunst ist ein Vehikel, auf dem wir glücklicher- weise leben können, und jeder kann sich in diesem Vehikel seinen Platz suchen. Das ist für die Maler, die wie die Teufel malen, genau- so toll wie für die Bildhauer, und das ist es auch für die Aktionskünstler. Wir haben alle Platz auf diesem Floß der Kunst, nicht wahr?

Christa Steinle: Der Platz ist da, ja. Der eine nimmt eben mehr Platz ein, genau- so wie ihre Installation, und erregt dadurch auch mehr Echo, mehr Resonanz im Publikum und auch durch die Medien. So spektakulär zu malen, ist ja sehr schwierig.

HA Schult: Naja, die Eiszeitmalerei – natürlich, da gab‘s ja noch keine Grüne Partei damals, und es gab auch noch keine SPÖ oder die Vorgänger der Regierung bei euch, sondern es gab nur die Kunst, und da gab es nicht mal die Kleine Zeitung. Oder den Observer. Und insofern konnten diese Künstler auch ohne Medien leben. Wir sind das Medium, das die Botschaft weiter trägt.

Christa Steinle: In jedem Fall, aber Ihre Kunst erregt ja nicht nur die Medien, Sie wollen damit ja auch eine Botschaft transportieren. Das sind ja nicht nur Skulpturen an sich, wie man sie natürlich auch auffassen kann. Sie entscheiden ja den Entstehungsprozess dieser so genannten Müllmänner mit, Sie bestimmen deren formalästhetische Lösungen, dass sie z.B. nur aus Coladosen bestehen sollen. Ihre ganze Kunst scheint mir ja auch aus einem ökologischen Bewusstsein heraus ent- standen zu sein, schon lange bevor es die Grüne Bewegung gegeben hat. Ich denke nur an Ihre erste große Aktion 1969, als Sie in München in der Schackstraße 5 Tonnen Altpapier aufgetürmt haben und damit praktisch die Straße verstopft war. Ist das in Analogie zu der Aktion von Joseph Beuys zu sehen, der nach einer Studentendemonstration den Müll zusammengekehrt und das dann in die Galerie von René Block in Berlin gebracht hat und einen gol- denen Besen dazu, oder auch Christo wäre zu nennen, diese Barrikade aus Ölfässern – in diesem Kontext ist doch Ihre Kunst zu sehen, nicht wahr?

HA Schult: Das ist schon richtig, aber ich würde statt Beuys Peter Weibel nennen. Beuys hat zu der Zeit noch Zeichnungen gemacht und war Assistent bei Mataré, und hat an der Ostfront des Kölner Doms mit- gearbeitet, das nenne ich nicht gerade Umweltkunst. Das war zur gleichen Zeit, als Peter Weibel an der Leine von Valie Export am Stephansdom vorbei auf allen vieren gelaufen ist. Das war so ungefähr die Zeit, in der ich eine Straße mit Müll zugeschüttet habe, und in der ein ganz anderer Künstler, der sich dann leider selber so ver- kitscht hat, über das Thema Umwelt in die Umlaufbahn der Medien trat, nämlich ihr Landsmann Hundertwasser. Er hat ja mit dem Verschimmelungsmanifest sehr stark über das Thema Umwelt geredet, während Joseph Beuys damals noch gemalt oder gezeichnet hat. Erst 1972, lange Jahre, also drei Jahre später – die zählen in der Kunst dann doch schon – ist Beuys auf den Zug der Grünen Partei aufge- stiegen, dadurch wurde das schon recht populär, und er hatte sicher – das muss man ihm auch zugestehen – eine sehr ökologische Vergangenheit, er hat auf dem Acker bei der Familie Van der Grinten gearbeitet, aber ich weiß nicht, ob Kohl zu ernten schon etwas mit Umweltkunst zu tun hat. Da war der Weibel viel weiter.

Christa Steinle: Das Verschimmelungsmanifest von Hundertwasser war Ihnen also vertraut?

HA Schult: Oh ja, auch Hundertwasser war mir sehr vertraut.

Christa Steinle: Schimmel war ja auch ein Thema Ihrer Aktion in Leverkusen, in Schloss Morsbroich, wo Sie in Reagenzgläsern Schleimalgen und Mikroorganismen, Bakterien vorgeführt und das ganze Museum in ein biochemisches Revier verwandelt haben.

HA Schult: Ja, mit Schimmel hatte Hundertwasser damals sehr viel am Hut, und auch ein anderer Künstler, nämlich Diter Roth. Der hat z.B. Bananen verschimmeln lassen, um uns klar zu machen, dass das auch ein Prozess ist, wenn eine Banane verschimmelt, und in der Zeit habe ich eine Ausstellung in Leverkusen vorbereitet, der damaligen Chemiestadt Deutschlands. Ich wollte den Krieg der Mikroben vorführen. Ich hab nämlich das, was uns tagtäglich umgibt, sichtbar zu machen versucht. Das geschah folgendermaßen: Ich habe die Leverkusener Luft einer Nährsubstanz ausgesetzt, auf 100 Ytong-Sockeln, und diese Nährsubstanz hat die Luft aufgenommen und sich dadurch farblich verändert.

Praktisch hab ich in Leverkusen die Luft von Leverkusen ausgestellt. Dazu hab ich einen Raum mit neun Zentnern Kartoffelbrei angefüllt, das kam der Stadt sehr teuer. Ein anderer Raum war mit Pommes frites bedeckt, wegen der Struktur. Und ein Raum des Museums – ein ähnliches Haus wie dieses übrigens, nicht ganz so schön und nicht mit so einer Vergangenheit, der Tanzsaal, der war mit Blaualgen gefüllt. Ich habe den Boden mit einer Folie ausgelegt, ihn kniehoch mit Wasser gefüllt, und Blaualgen in diesem Wasser angesetzt. Blaualgen sind phototaktisch empfindlich, sie krochen auf die einzige Lichtquelle, die ich im Raum hatte, zu und wurden dann von den lebendigeren Algen abgedrängt. Auf dem Höhepunkt ihres Lebens waren sie kobaltblau, um dann wieder durch die lebendigeren in der Versenkung zu verschwinden.

Ich habe damit versucht, und ich hab‘s vielleicht auch ganz sinnlich getan, Leben und Sterben im Museum vorzuführen, in einer Art Zeitraffersystem. Dann hat ein Besucher in die Folie gestochen und diese ganze Brühe ist in die Decke gelaufen, und noch Monate hinterher konnte man die Reste meiner Ausstellung im Parkett betrachten, die Ausstellung war nicht tot zu bekommen, obwohl sie Leben und Sterben darstellte – da gabs natürlich eine Stadtrats-Sitzung, der Museumsdirektor wurde heftig angegriffen …

Christa Steinle: Sie nannten diese Ausstellung damals “Biokinetische Situationen“, waren Ihnen die französischen Situationisten vertraut?

HA Schult: Oh ja, auch die russischen Situationisten. Denn das, was ich mache, wenn wir jetzt wieder auf die Aktionskunst zurückkommen, das baut ja auch auf die Kunst der 20er Jahre in Russland oder auf die der Futuristen in Italien auf. Tatlin und all die anderen gingen ja auf die Straße mit öffentlichen Skulpturen, sie wollten der Umklamme- rung herkömmlicher Kunstgedanken entkommen, gingen auf die Straße, wurden dann missbraucht von den Politikern verschiedenster Richtung, Lenin, Stalin, später kamen der Duce und Adolf Hitler dazu. Aber die Auseinandersetzung mit der Schere im Kopf, die man nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg bei uns in Deutschland und anderswo vorfand, die fand ja erst in den 50ern und 60ern statt, und da ist das Stichwort Christo ganz wichtig, der in Paris eine Straße mit Ölfässern verbarrikadierte, das fiel genau in diese Zeit.

Christa Steinle:

Was sagen Sie zu Ihren Künstler-Kollegen, Günter Saree, Ulrich Herzog, Jürgen Claus? Die haben mit Ihnen kooperiert?

HA Schult: Ja, Günter Saree war ein konstruktivistischer Künstler, der ordentliche Bilder malte und dann an mich geriet, dadurch ein bisschen durcheinander kam und bei der Aktion Schackstraße mit dabei war. Er hatte sich damals noch nicht so gefunden, er hat dann später ein sehr konsequentes Frühwerk hinterlassen, mit einigen sehr schönen Aktionen; leider starb er sehr früh. Jürgen Claus lebt noch, er wollte Unterwasserkunst machen und ist Professor geworden, etwas Ordentliches eben. Und der Ulrich Herzog, der hat ein Taxifahrunternehmen aufgemacht. Er war nur kurz dabei; nicht zu verwechseln mit Werner Herzog, der immer noch in Deutschland lebt und Filme macht und sehr bekannt ist aus dieser Zeit.

Christa Steinle: Sie wurden dann ja immer als Biokinetiker apostrophiert, oder war das eine Kreation, eine Wortschöpfung, die Sie selbst für sich als Berufsbezeichnung gewählt haben, was ja darauf hindeutet, dass man über das Feld der Kunst hinaus geht in andere Prozesse, in Lebensprozesse.

HA Schult: Ja, die 50er Jahre waren in Deutschland sehr produktiv, genau wie in Österreich, da gab es diesen verdienstvollen Monsignore Mauer in der Galerie nächst St. Stephan in Wien, da gab es bei uns in Deutschland Alfred Schmela in Düsseldorf. Damals in Düsseldorf sahen wir ja nach dem Krieg die ersten Äußerungen von Künstlern, die in den Umraum, in den Alltag hinaus gingen, da gab es den Maler George Mathieu, der wie ein Verrückter im Schaufenster malte, in Paris und auch in Düsseldorf, da gab es diesen bewundernswerten, auch sehr früh verstorbenen Künstler Yves Klein, dann gab es Lucio Fontana, der die Leinwand zerstörte, und das alles hat mich geprägt.

An der Kunstakademie, die sie mir sehr ehrenvoll zugestehen, da habe gelernt, dass ich auch ein Häschen malen kann und eine Schildkröte, oder auch einen Akt, wenns drauf ankommt, an dieser Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, aus der man Paul Klee in den 30er Jahren hinausgejagt hat, und wo man sich nach dem Krieg mit wenigen vernünftigen Professoren erst einmal wieder finden musste. Die RheinRuhrCity war ein Schmelztiegel, auch durch das Geld, das sich da versammelte für die Künstler aus Frankreich, aus Belgien, auch aus den USA; viele Karrieren, z.B. die von Andy Warhol oder von Bob Rauschenberg, sie alle begannen in RheinRuhrCity, in der riesigen Landschaft von Dortmund über Krefeld, Leverkusen bis nach Bonn, wo einer der größten kulturellen Ereignisteppiche nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg in Europa entstand.

Christa Steinle: Sie haben Yves Klein genannt, könnte man nicht eine gewisse Parallelität sehen, diese Obsession für das Auto, die Sie ja auch gewissermaßen in Ihrer Aktion entwickelt haben, bei der Sie Deutschland durchquert haben, Zehntausende von Kilometern. Yves Klein ist doch auch mit der Leinwand auf seinem Auto durch die Landschaft gefahren, und die Spuren, die die Luft und das Wasser auf der Leinwand hinterlassen haben, waren eben das approbierte Kunstwerk.

HA Schult: Ja gut, dass sie das sagen, denn das ist mir ganz entfallen. Mir fällt das im Nachhinein auf – in meinem Buch steht das nicht drin, aber mir fällt das jetzt auch auf, genauso wie es mir als Künstler erst auffiel, nachdem ich diese 1000 Skulpturen gemacht hatte, was die mit der Terrakotta-Armee in Xiang zu tun haben. Wir Künstler machen ja oft Sachen, bei denen wir gar nicht wissen, aus welchem Fundus wir schöpfen. Wir müssen das nur zugeben – und ich habe das bereits versucht zuzugeben mit der Rede von der Eiszeit, die ja viele Künstler beeinflusst hat – weil wir alle auf dem Boden der Vergangenheit stehen und aus alldem heraus schöpfen. Richtig: Yves Klein hat diese Aktion gemacht, an die ich mich jetzt auch wieder erinnere, ich bin 20 Tage 20.000 Kilometer gefahren, 1970 war das, also Jahre nach Yves Klein, und ich habe die Windschutzscheibe täglich auswechseln lassen, weil sie ja der Beleg der Fahrt waren – es ist der originäre Schmutz der 60er Jahre, jedes Insekt, das darauf verewigt ist, das ist authentisch.

Aber worauf es mir ankam, war der Prozess: Yves Klein war doch immer noch im allerbesten Sinne ein traditioneller Künstler, der uns einen so großen Phantasierahmen gab, dass ich mich darin zugegebenermaßen auch bewegen konnte. Aber Yves Klein strebte natürlich doch noch das vollendete Bild an.

Er war ein Meister, das zu vollenden, indem er eben mit seinen blauen Bildern einen Schlussakkord setzte. Das war nicht mein Ding. Mein Ding war der Prozess, der Vorgang, der Wahn der Autobahn, das Sich-Hingeben auf der Autobahn, nämlich dass wir nicht mehr in der Steinzeit leben, sondern in der Stauzeit; und so leben wir auch nicht mehr nur in der Stauzeit, sondern wir leben auch in der Müllzeit. Auf jenem Planeten Erde, den wir gemeinsam im Begriff sind zuzumüllen, obwohl er uns nur leihweise überlassen wurde. Das wurde mein Thema, und da gibt es natürlich Künstlergestalten, auf die ich aufbaue, vor allem Arman, der ja sehr früh mit Müll oder mit Resten gearbeitet hat, dann natürlich mein Freund Bob Rauschenberg, der damals, 1958, zum ersten Mal in Europa in Düsseldorf ausstellte, und der mich sehr stark geprägt hat, was ich ihm auch immer gesagt habe. Diese Kunstform des zersetzenden Prozesses, des Wahns, in dem wir leben, das wiederzugeben, das wollte ich.

Und wenn man heute sieht, wie Models in Afrika über den Laufsteg gehen, unter denen sich der Müll abspielt, so ging man 1969 in Schloss Morsbroich über den Kartoffelbrei oder über die Mikroorganismen. Über den Krieg der Mikroben, wie das einmal ein Kritiker nannte. Das alles hat mich bis heute begleitet, natürlich mit einem anderen Atem, denn das, was ich mache, ist sehr aufwendig, es sind 1000 Skulpturen, die ich gebaut habe. Ich habe 2000 gemacht, 1000 verkaufe ich, um den Trip zu finanzieren, und 1000 sind die Reisenden. Wenn einer gereist ist und verkauft wird, rückt ein neuer nach. Zuhause ist so ein Trash Man sehr angenehm, er widerspricht nicht, er ist ideal für Singlehaushalte, und man fühlt sich nicht so alleine, und immer ist jemand da, mit dem man das eine oder andere Wort zwar nicht wechseln, aber den man ansprechen kann.

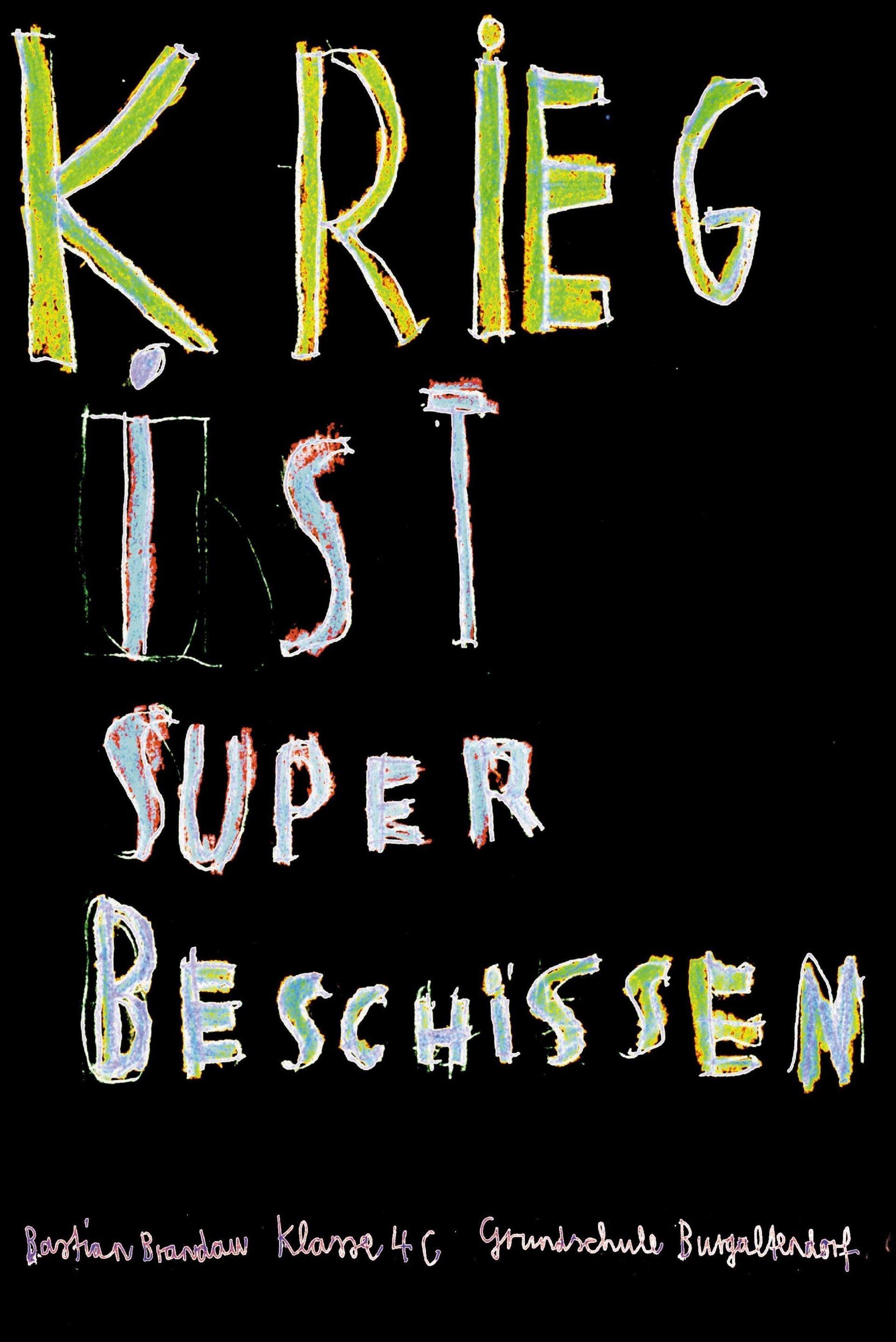

HA Schult - War ©HA Schult

HA Schult - War ©HA Schult

Christa Steinle: Gehen wir über zur documenta 5, 1972, die auch großes Aufsehen erregt hat aufgrund ihrer Aktion mit den Soldaten. Können Sie das vielleicht ein wenig erklären?

HA Schult: Damals war ich ein junger aufstrebender Künstler, und hatte eine Idee für die documenta, die von Harald Szeemann gemacht wurde, jenem legendären Mann, der sich aus der Museumslandschaft heraus in die Kuratorenlaufbahn entfernt hat. Für Harald Szeemann war die documenta 5 ein Durchbruch und Beweis, dass man nicht unbedingt im Dienste eines Hauses stehen muss, um Kunst zu vermitteln, sondern dass man auch als Freelancer arbeiten kann. Heute gibt es viele solcher Kuratoren, er war, kann man sagen, der erste, der mit der documenta 5 ein Zeichen setzte. Er war ein sehr liberaler Mann, war eigentlich gelernter Schaufensterdekorateur, was immer unter den Tisch kommt, aber warum auch nicht. Und er lebte in einem ziemlich engen Radius, aber dreisprachig in Bern. Da hat er zum ersten Mal das Kunstmuseum einpacken lassen, von meinem Kollegen Christo. Und dann machte er die documenta, sehr elitär auf der einen Seite, ganz mit seiner Handschrift, und ich wurde eingeladen, was für mich sehr wichtig war, denn – auch wenn ich heute recht bekannt bin – man muss in Museen ausstellen, damit die normalen Menschen glauben, dass das Kunst sei.

So hab ich zweimal an der documenta teilgenommen, und meine Werke hängen auch – wenn ich das sagen darf – in annähernd 60 Museen auf der Welt. Harald Szeemann lud mich damals ein, mit einem seriösen Beitrag an der documenta teilzunehmen, und ich habe dann, sehr unseriös, einen lebenden Soldaten ausgestellt, der leere Coca Cola-Flaschen bewachte. Das hatte schon seinen Sinn. Denn mit Coca Cola beginnt jeder Krieg seit dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Zuerst war Coca Cola in Vietnam oder in Korea. Heute ist es auch McDonald‘s. Auch in Beirut und in Afghanistan, das ist logisch, die Amerikaner sind so gewöhnt an diese Droge Burger, die muss natürlich den Krieg begleiten, und Coca Cola auch.

So habe ich ganz bewusst Coca Cola-Flaschen dort gezeigt – dann ergab sich etwas sehr Verrücktes, das auch die Archäologie der Gegenwart betrifft, meine Kollegen aus den USA haben die Flaschen immer wieder geklaut. Weil das so ein Klassiker war. In Amerika wurden solche Flaschen nicht mehr hergestellt, das waren diese gebuckelten Flaschen, wo der Schriftzug noch eingeformt war. Der Berg von Coca Cola-Flaschen wurde immer kleiner, die berühmtesten Künstler haben sich erdreistet, da in die Flaschen zu greifen, als archäologisches Fundstück der Gegenwart. Das hab ich ja nun hier auch erlebt, bei meinen Skulpturen im Innenhof, da lief jemand von Red Bull verwirrt hier herum, weil da keine Red Bull-Dose dazwischen ist. Dazu muss man sagen, dass es, wie ich angefangen habe, die Skulpturen zu machen, in Deutschland noch kein Red Bull gegeben hat. Der Erfinder hat innerhalb von zehn Jahren eine Weltkarriere gemacht, und das ist eben auch eine Parabel für die Archäologie der Gegenwart, denn die zerquetschte Red Bull-Dose von heute ist die römische Scherbe von morgen.

Auf einem der in dieser Ausstellung gezeigten Bilder sieht man ein Loch in der Nähe von Kairo, in Luftlinie ungefähr 10 Kilometer von den Pyramiden von Gizeh entfernt, und in diesem Loch liegt der Müll. Das Loch hat einen Durchmesser von vielleicht 800 Metern oder einem Kilometer. Die Ägypter haben eine tiefe Grube gegraben und da schmeißen sie den Müll hinein. Der Müll ist vorher, vor den Haustüren, schon von den Ärmeren ausgewertet worden, die haben ihn mit nach Hause genommen. Wenn man die Menschen dort besucht, dann sind die Wohnungen oft voller Müll. Der Müll wächst bis aufs Hausdach, denn die Familie wertet ihn aus, und wirft den Rest dann wieder vor die Tür, dann kommen die noch Ärmeren und nehmen wiederum diesen Müll. Am Schluss landen die Müllreste in einem riesigen Loch, in diesem Loch leben Menschen, die von dem Müll leben, der dort abgeworfen wird, und die ihn dann wiederum auswerten. Darum herum sind hunderte von Hunden, die balgen sich wiederum um diese letzten Reste vom Müll. Man steht da oben und blickt auf die Flammen herunter, weil es oft Brände gibt durch die Sonne. Nach drei Jahren wird dieses Loch mit Sand gefüllt werden und zwei Jahre später steht darauf ein Holiday Inn oder ein Golfplatz. Das ist ein Kreislauf, für uns ist es unvorstellbar, wie man mit diesem Müll dort hantiert.

Während wir hier die teuersten, aufwendigsten Müllverbrennungsanlagen bauen, machen die das auf die lockere Art, ähnlich wie die Russen, die die ausgebrannten Atombrennstäbe in die Vorgärten der westlichen Welt werfen. Das ist eben auch eine Begleiterscheinung dieser Aktion, das aufzuzeigen, wie man in China oder in Russland, in der Schweiz oder in Österreich, in Deutschland oder aber eben in Ägypten ganz verschieden mit diesem Thema umgeht. Das ist meine Idee einer globalen Skulptur, an der ich den Zustand aufzeige, mit dem man jenes Thema behandelt, das uns alle die nächsten Jahrzehnte entscheidend prägen wird, nämlich das Thema Müll.

Christa Steinle: Also Zivilisationskritik. Das war es dann auch sicher, als Sie den Markusplatz mit Tonnen von Papier bedeckt haben. Das ist ja durch alle Medien gegangen, auf der Titelseite, es war mehrfach gecovert …

HA Schult: Ja, das war ‘ne geile Aktion. Das war 1976, da war ich schon recht bekannt und auch verrufen, hing aber schon in zahlreichen Museen mit meinen Picture Boxes, war also schon ehrenwert. Aber nun stand ich nachts auf dem Markusplatz, der ja ein Symbol der stillstehenden Zeit ist. Jeder, der da einmal stand, ob aus Australien oder aus China, aus Deutschland, Österreich, oder wo er auch herkommt, nimmt das stillstehende Bild des Markusplatzes mit nach Hause. Das ist der Salon Europas, einer der schönsten, wenn nicht der schönste Platz der Welt.

Und ich hab gedacht, wenn ich in diesen Platz hinein das von uns Ausgespieene, Ausgekotzte, von uns Verursachte werfe, könnte ich das Thema Umwelt vielleicht etwas deutlicher darstellen als der eine oder andere Kongress der UNESCO. Und das ist auch gelungen. Denn ich habe in ein Behältnis der Vergangenheit die Gegenwart gekippt, und die so nahe Zukunft, 1976, und das fand seine Reaktionen in der Vatikan-Zeitung genauso wie in der Bild-Zeitung, in der Kronen Zeitung genauso wie in der Prawda. Das war, wie sie ganz richtig am Anfang dieses Gesprächs anschnitten, natürlich eine Medienskulptur: es sind Bilder, die in den Medien die Menschen so ansprechen, dass sie sie im Kopf behalten. Und das ist das Gute an dieser Kunst, dass sie auch in den Köpfen jener Leute stattfindet, die sich normalerweise in die Museen, aus welchen Gründen auch immer, eben noch nicht bewegt haben. Ich ziehe ja auch Menschen in das Museum rein, die normalerweise da nicht hinein finden. Und das ist ein Dialog, auf den ich auf eine gewisse Weise auch stolz bin, und den ich mit liberalen Museumsdirektorinnen und -direktoren teile.

Christa Steinle: Aber darüber hinaus müssen Sie ja ein Meister der Logistik sein – normalerweise tut sich Kunst im öffentlichen Raum ja sehr schwer, sich zu situieren, vor allem ist es schwer, überhaupt die ganzen Bewilligungen zu bekommen. Allein wenn wir eine kleinere Aktion starten möchten, ist das oft mehr als mühsam.

HA Schult: Wie ich zum ersten Mal in China auf die Mauer wollte, brauchte ich natürlich Monate, ja eigentlich Jahre, um so eine Genehmigung zu bekommen. Um auf dem Roten Platz zu stehen, wenige Jahre nach der Perestroika, mit 1000 Skulpturen, um auf der Chinesischen Mauer zu stehen, in einem Land, in dem moderne Kunst über Jahrzehnte, über Jahrhunderte verpönt war, um in dem von Terrorismus immer wieder heimgesuchten Ägypten zu stehen, das sind lange Prozesse. Da muss man natürlich, und das ist das Schöne an dieser Kunst, vom Parkplatzwärter, vom Zollbeamten bis zum Staatspräsidenten mit jedem reden. Und das bewirkt auch die Dynamik dieser Kunst, dass sie nämlich über normale soziale Schranken hinweg funktioniert, aber natürlich nur wenn das Thema funktioniert, das ist ganz wichtig, und mein Thema, das ist in jedem Land klar, ist das Kernthema unserer Epoche.

Christa Steinle: Ich denke mir, am Roten Platz muss es ja besonders schwierig gewesen sein. Wie konnten Sie Putin da überzeugen?

HA Schult: Also, ich hab auf dem Roten Platz keine Genehmigung gehabt und auch in China nicht. Ich will ihnen das gern an diesen zwei Beispielen erzählen, wie schwer das ist. Ich habe 1994 in St. Petersburg gearbeitet und zwei Panzer dort auf jenen Platz gestellt, auf dem 1917 eine Revolution ausgebrochen ist, die uns bis heute beschäftigt, nämlich die Oktoberrevolution. Und auf diesem Platz, in einer Stadt, die von Hitler im Zweiten Weltkrieg um eine Million Menschen gebracht wurde, die er verhungern ließ durch seine ewige Blockade, wollte ich als deutscher Künstler den Schriftzug “Der Krieg“ zerreißen.

Um diese Genehmigung zu bekommen, geriet ich durch den damaligen Oberbürgermeister an einen zweiten Bürgermeister, ich will das jetzt nicht zu weit führen, aber als Beispiel nehmen, wie man so ein weltweites Netzwerk haben muss. Und so war das damals in St. Petersburg, als Herr Sobtschak mich zu seinem Stellvertreter schickte. Das war ein untersetzter Mann, nicht größer als ich, er hatte Augen wie eine Eidechse, war sehr athletisch gebaut und sprach fließend deutsch mit einem kleinen sächsischen Einschlag, weil er KGB- Angestellter in Ostdeutschland gewesen war, um dort Wirtschaftsspionage zu betreiben. Und mit dem entwickelte ich eine Freundschaft, da kam ich ja nicht umhin, sonst hätte ich das nicht machen können, und er hat mir seine Vergangenheit erzählt. Man kam in Russland nur über den KGB nach oben, während man in New York, sagen wir einmal, boxen oder Soul singen kann, um aus der Unterschicht nach oben zu kommen, oder mit Drogen handeln, das war ja alles in Russland nicht möglich. In Russland ging man eben zum KGB. Und so entwickelte sich eine Freundschaft, ich bekam die Genehmigung, dafür habe ich 60.000 Dollar bezahlt, damit Behinderte in St. Petersburg auf dem Newski-Prospekt herunter rollen können und nicht mehr nur auf die Treppen angewiesen sind; das war meine Stiftung, um die Genehmigung zu bekommen, auf dem Schlossplatz den “Krieg“ zerreißen zu dürfen. Diese Behindertentreppen sind bis heute nicht gebaut, aber bezahlt habe ich sie schon mal. Und dann später war ich in Moskau damit beschäftigt, auf den Roten Platz zu kommen, das war dann ‘99. Die vom Touristikministerium haben mir die Stadt gezeigt. Da kamen wir auch am KGB vorbei und ich fragte einen meiner Begleiter, wer denn jetzt Chef sei und da nannte er mir einen Namen. Ich rief sofort in Deutschland an und sagte: Ruft mal eben den Mann an, ob die Handynummer noch funktioniert, denn ich kannte ihn ja aus St. Petersburg. Und sie funktionierte noch.

Die Elke rief an und sagte ihm, der HA braucht dich, komm doch mal in sein Hotel. Und da kam er in mein Hotel und die Straße wurde gesperrt, da waren Fahrer mit Kalaschnikows, und in der Hotelhalle wurde alles still gelegt – es gab gerade ein Filmfestival, Alain Delon, der berühmte französische Schauspieler, musste anderthalb Stunden aus Sicherheitsgründen im Lift bleiben – und wir aßen zusammen zu Mittag. Da habe ich ihn gefragt, ob ich noch eine Genehmigung brauche, denn ich hatte ihn ja ‘96 so gut kennen gelernt, und er hat gesagt: Du nicht.

Und so hatte ich nie eine Genehmigung und habe die Trash People einfach auf den Roten Platz gestellt. Aber alle wichtigen Leute wussten, dass er bei mir zum Mittagessen gewesen war. Er wurde dann ein halbes Jahr später Staatsoberhaupt. So kann man natürlich ein Projekt realisieren; wenn man auf den Falschen setzt, funktioniert das weniger. 1986 hatte ich einen Termin bei Deng Xiao Ping, um in China einen Berg aus europäischer Erde zu bauen. Ich wollte in die Verbotene Stadt einen Berg stellen, und wollte aus allen Ländern Europas Erde heranschaffen, um daraus einen Berg zu bauen. Die Chinesen sollten durch den Berg hindurch gehen, womit ich sie gewissermaßen durch Europa schicken wollte.

Und er sich das angehört, ganz kurz, ich hatte 20 Minuten, davon haben sie mich 15 Minuten durch die Gänge gejagt, dann blieben fünf Minuten für das Gespräch – und danach wurde mir mein Visum entzogen. Er hatte mir bei diesem Besuch gesagt: Das findet hier nicht statt. Sie gehen als Chinesen rein und kommen als Europäer raus.

Und so kann man dann auch schief liegen. Dann, 2001, standen die Skulpturen auf der Chinesischen Mauer, denn die Chinesen wollten 2008 die Olympiade veranstalten, und da haben sie mich benutzt, um ihre neue Liberalität zu bezeugen, und ich hab mich gerne benutzen lassen, um dieses Projekt durchzusetzen. Das ist immer ein Fenster, ein politisches Fenster, ein soziales Fenster, manchmal wird es, wie z. B. bei der Aktion Der Krieg wieder schnell zugeschlagen, denn kurz darauf zogen die Russen in den Tschetschenien-Feldzug, damit war es aus mit dem Frieden.

Aktion in St. Petersburg ©HA Schult

Christa Steinle: Vom Roten Platz zurück nach New York – das war eine Aktion, die Sie für die documenta 6 mit Schauplatz New York gewählt haben, eine Arbeit unter dem Titel Crash, in der sie bei der Freiheitsstatue ein Flugzeug abstürzen ließen – eine fast prophetische Arbeit, könnte man in Hinblick auf den 11. September sagen. Per Satelliten wurde das zeitgleich auf die documenta übertragen. Sie haben diese Aktion A Monument of Our Time genannt, so ähnlich wie Tinguely auch die selbstzerstörerische Maschine 1960 im Garten des MoMA benannt hat. Wenn ich an die Fotos dieser Aktion – das Flugzeug zwischen den Zwillingstürmen – denke …

Damals haben Sie ja bereits von der Medienskulptur gesprochen, warum haben sie das so genannt? Aufgrund dieser Übertragung auf die documenta?

HA Schult: 1977 zog ich nach New York, und bekam die Einladung, auf der documenta 6 einen Beitrag zu leisten, und hatte die Idee, den Traum vom Fliegen, der seit Leonardo ja von Künstlern geträumt wurde, in Frage zu stellen. Man muss zu meiner Rechtfertigung sagen, es gab zu der Zeit kein Hijacking, keine Flugzeugentführung, das kannte man noch gar nicht 1977. Und so kam ich auf die Idee, ein Flugzeug, tätowiert mit den Insignien des Konsums, Coca Cola und Marilyn Monroe in diesem Fall, und einer amerikanischen Flagge um die Alpen des Kapitals fliegen zu lassen, die Skyscraper von New York. Das World Trade Center war wenige Jahre alt, und diese Maschine umkreiste das World Trade Center, flog hinüber zur Freiheitsstatue und stürzte sich dann auf die größte Müllhalde der Welt zu der Zeit, Staten Island. Staten Island ist nicht wie andere Länder, wie Ägypten, wo ein Loch gegraben wird, oder wie in Deutschland, wo ein Berg geschaffen wird, sondern das ist ein Landgewinnungsprojekt. Bei Staten Island ist durch Müll Land gewonnen worden, das ist eine riesige Mülllandschaft, oder war es damals, jetzt sind da Häuser drauf, aber es ist immer noch eine Müll-Landschaft.

Da wollte ich das Flugzeug abstürzen lassen und habe das mit dem Piloten festgelegt, der ein sehr professioneller Pilot war. Er wurde als Armeeangehöriger zwei Mal abgeschossen und hat dafür nicht mehr als einen Orden bekommen. Von mir hat er 60.000 Dollar bekommen, damit er diesen Absturz auch wirklich macht. Ich habe eine Cessna gekauft, habe diese Cessna über Manhattan fliegen lassen und sie dann auf die Müllkippe stürzen lassen. Der Absturz ist die Skulptur, eine auf tausendstel Sekunden gebaute Skulptur, die von dem selben Fotografen, jetzt kommen wir wieder zu Yves Klein, fotografiert wurde, der den berühmten Fenstersprung von Yves Klein, der uns vormachen sollte, als Künstler könne man auch fliegen, fotografiert hat: Harry Shunk. Und dieser Aufprall wurde fotografiert, der Pilot hat das überlebt, der konnte so was; wir haben unten auch die Aufprallstelle unterfüttert.

Wir hatten ja damals keine Computerberechnungen, keine Handies, das war ja alles ganz anders damals. Diese Satellitenschaltung war sehr aufwendig; es war die erste Satellitenübertragung einer Kunstaktion überhaupt, denn zur gleichen Zeit, als ich das machte, war in Kassel auf der documenta am Herkules, ein Monument einer anderen Epoche, die Aktion zu sehen. Und sie hieß Crash, ein Monument für die Vereinigten Staaten und ich habe dieses Flugzeug dem Müll beigegeben. Das Makabre daran ist, bei 09/11 ist dann der Müll vom World Trade Center vom CIA und FBI nach Staten Island geschafft worden und die Reste vom World Trade Center liegen heute auf meinem Flugzeug. Das ist eine Sache, die kann kein Künstler machen. Aber bei der Panik, die in Amerika besteht in Bezug auf die Immigration, da achte ich immer darauf, dass diese Fotos nicht auftauchen, sonst kommt man noch auf falsche Ideen. Meine Aktion ist eine Parabel dafür, dass wir Künstler am Puls der Zeit sein müssen, um Menschen etwas zu zeigen, was sie alle angeht.

Christa Steinle: 1985 gab es eine weitere Aktion in New York, als Sie vor den Türmen des World Trade Centers das Brandenburger Tor postiert haben, sozusagen eine Replik. Auch hier gab es eine Satelliten- Fernsehübertragung der New Yorker Mauer auf die Berliner Mauer. War das eine Art Doppelkritik bzw. Konsumkritik an New York, als Türme des Kapitals, wie sie dann auch Beuys genannt hat, Cosmos und Damian, und an der Mauer der Kommunistischen Ideologie?

HA Schult: Also, 1985 konnte sich niemand auf der Welt vorstellen, dass 1989 die Mauer fällt. 1985 hab ich die Berliner Mauer in New York rekonstruiert, am Exchange Place, wo die Yuppies immer, wenn sie aus der Börse ausgespieen werden, abends in die Vororte fahren. Dort habe ich den Platz mit der Mauer versehen, und habe sie nach den Rezepten von Walter Ulbricht und Genossen rekonstruiert. Dann hatte ich das Brandenburger Tor zu Füßen des UNO- Gebäudes gestellt, als Replik, 12 Meter hoch, mit der Quadriga, die die Besucher anguckte. Man konnte zu der Zeit in West-Berlin nur die Quadriga von hinten sehen, nicht von vorne. Heute, Unter den Linden, können Sie das. Ich habe sie aber so gebaut, dass man sozusagen in Ostberlin stand und dahinter stand das UNO-Gebäude, und ich hab den Leuten, die bei der UNO arbeiteten, in ihre Briefkästen die Botschaft gesteckt, dass ich die Grenze zwischen Ost und West für ein Monat verrückt hätte. Das Ganze geschah auf Einladung des Guggenheim Museums und des damaligen Direktors Tom Messer. Ich fuhr täglich mit einem echten doppelstöckigen Berliner Omnibus vom Museum los und behauptete, New York sei Berlin. Und Bloomingdales sei das KaDeWe und St. Patrick’s Cathedral sei die Gedächtniskirche, und dann fuhren wir zum Brandenburger Tor und da sahen wir ja, dass Berlin in New York stattfand. Wir fuhren vom Brandenburger Tor dann zum Exchange Place, wo die Berliner Mauer stand, genau rekonstruiert aus Beton.

Die New Yorker sagten: Das kann doch gar nicht wahr sein, so eine Mauer soll durch die ganze Stadt gehen? Obwohl sie das im Fernsehen gesehen hat- ten, davon gehört hatten, erst wenn man so ein Ding anfasst, wenn man daran klopft, erst dann versteht man oft den Wahnsinn, und so haben sie gesagt: Was? Durch die ganze Stadt?

Bei der Pressekonferenz im Guggenheim Museum fragte jemand von der Daily News, warum meine Mauer so kurz geraten sei. Und ich habe gesagt: Weil ich kein Staatsoberhaupt bin, das die Mauer auf den Schultern seiner Bürger austrägt und bezahlt. Denn das einzige, was die DDR hervorgebracht hätte, seien der Bau der Mauer und die Rekonstruktion des Zwingers in Dresden. Daraufhin hat die DDR bei den Amerikanern Protest eingelegt wegen Verunglimpfung ihres Landes. Die DDR hatte Besitzanspruch auf die Mauer angemeldet, zu Recht, denn sie stand etwas hinter der tatsächlichen Grenze, davor gehörte auch noch ca. anderthalb Meter Grund zu Ostdeutschland. Ich wollte die Berliner Mauer in New York auf die Berliner Mauer in Berlin projizieren, dagegen hatte die DDR bei den Amerikanern Protest eingelegt, denn die Mauer gehöre ihnen. Rechtlich ist die Sache relativ simpel, bei uns wenigstens in Deutschland: wenn ich eine Taschenlampe auf Sie richte, und Sie erheben Einspruch, dann darf ich das Licht nicht auf Ihr T-Shirt fallen lassen. Das ist Ihr Körper. Es gab dann eine endlose Geschichte zwischen den Amerikanern und der DDR nur wegen dieses Projekts. So habe ich dann eine Mauer vor der Mauer in Westberlin errichtet, aus Monitoren, auf die ich die Mauer aus New York übertragen habe. Gleichzeitig, das war 22 Uhr in Berlin, und 4 Uhr nachmittags New Yorker Zeit, sangen ein Tenor der Berliner Oper und ein Tenor der New Yorker Oper die Florestan-Arie aus Fidelio.

Und in Deutschland sah man auf den Bildschirmen beide Sänger parallel und wusste nicht, ist das die Berliner Mauer in Berlin oder ist das die Berliner Mauer in New York? Und dann erst zog die Kamera hoch und hinter der Berliner Mauer in New York kamen die Zwillingstürme der kapitalistischen Welt zum Vorschein und hinter der Berliner Mauer in Ostberlin war alles finster.

Christa Steinle: Ausgehend von der Chinesischen Mauer sind wir nun also mit den Müllmännern in diese Containersituation im Palais Herberstein geraten, ich glaube, auch das hat großes Echo ausgelöst.

HA Schult: Hier ist es auch sehr schön, weil die Skulpturen zum ersten Mal nicht in so einem großen Umfeld stehen. Hier sind nur hundert, tausend geben natürlich ein bisschen mehr her, aber sie sind sehr schön hier und heute abend sehr berührend, weil es regnet, und das Pflaster da mitspielt, und weil sie in einem Behältnis stehen, wie damals bei der Aktion auf dem Markusplatz, in einem Behältnis stillstehender Zeit ruhen.

Giza Pyramiden, Kairo, 2002 ©HA Schult

Stellisee, Zermatt, 2002 ©HA Schult

Matera, 2019 ©HA Schult

Matera, 2019 ©HA Schult

Matera, 2019 ©HA Schult

Matera, 2019 ©HA Schult

Chinesische Mauer, 2001 ©HA Schult

Trash People Simulation in Australien ©HA Schult

Christa Steinle: Die nächste Station ist die Piazza del Popolo in Rom?

HA Schult: Ja, das ist die nächste Station. Das sind dann alle 1000 Skulpturen, ebenso ist es geplant, sie in New York aufzustellen und im darauf folgenden Jahr in der Antarktis, das ist die letzte Station. Dann habe ich an etwa 20 Schauplätzen gestanden, und diese Schauplätze sind alle irgendwie mit der Kulturgeschichte, der Weltgeschichte, der Politik verwoben. Das ist meine Idee einer globalen Skulptur.

Christa Steinle: Ich hätte noch gerne eine andere Arbeit angesprochen, Gorleben, als Sie in einem Atomarchiv sozusagen, der Endlagerung für Atommüll, eine Aktion gesetzt haben, die, obwohl so spektaklär, doch mit einer sehr großen Sensibilität gegenüber diesem Thema entwickelt wurde.

HA Schult: Ja, nachdem sie unter dem Matterhorn standen, in 2700 Metern Höhe, hatte ich die Idee, sie an einen Ort zu bringen, der uns in Deutschland im Moment sehr beschäftigt und der in der Welt der einzige Versuch ist, die Atombrennstäbe wenigstens vernünftig zu entsorgen. Denn weder die Amerikaner noch die Russen machen sich darüber ernsthafte Gedanken. Die Deutschen haben sich Gorleben aufgeladen und für 1,5 Milliarden Euro ein Endlager gebaut, das aber aufgrund politischer Positionen nicht bespielt werden kann, das ist in 880 Meter Tiefe in diesem Ort Gorleben. Ich hatte die Idee, diesen Ort einmal aus einem anderen Blickwinkel zu sehen und nicht so vordergründig nur durch Demonstrationen zweimal im Jahr. So wie bei uns in Deutschland der Karneval stattfindet oder das Oktoberfest, finden in Gorleben Demonstrationen statt. Die Teilnehmer sind schon abgestumpft; eine Generation von Demonstranten, die auch schon ihre Kinder dazu erzogen hat, zu demonstrieren. So wird das zum Ritual, und dann heißt es, jetzt müssen wir schon wieder nach Gorleben. Auch die Redaktionen, vom Spiegel bis zum Stern, oder die großen Agenturen schicken nur mehr Azubis dort hin, denn darüber haben sie sich bereits die Finger wund geschrieben. Es war aber auch das Bestreben der Politik, dieses Thema immer unter den Teppich der Verdrängungen zu kehren.

Deswegen dachte ich mir, ich gehe dorthin, um einen anderen Blickwinkel darauf zu werfen und habe 800 Skulpturen auf jener Straße aufgestellt, durch die die Transporte normalerweise gehen und 200 Skulpturen in 880 Metern Tiefe. Das war die teuerste Kunsthalle der Welt, 1,5 Milliarden Euro hat der deutsche Staat dafür ausgegeben, denn etwas anderes ist da bisher nicht geschehen. Wir Künstler können Hinweise geben, aber wir können – und das ist vielleicht das Schlusswort – den Zeitfluss nicht verändern. Wir können die Gedanken der Menschen beeinflussen, aber nicht ihr Tun.

————

Christa Steinle, promovierte Kunsthistorikerin, und ehemalige Direktorin der Neuen Galerie Graz am Landesmuseum Joanneum, ist Herausgeberin zahlreicher Publikationen und Veranstalterin zahlreicher Ausstellungen zur Kunst des 19. bis 21. Jahrhunderts.

HA Schult: HA Schult Museum

Mehr über diesen Künstler

Brothers Gottschalk visiting the Trash people army on the Great Wall @HA Schult

Art & Environment 2022 - By C. Mauer

Art, Vision and Investment - "Art is Life" - HA Schult's Plans for the Zeughaus Köln and the City of Cologne. "Art is Life Building" and "Art is Life Cologne".

HA Schult in Munich, 1969. The Day, Trash Art was born ©Thomas Lüttge

Art Calendar, Environment, October 19, 2022

HA Schult news - for the "Festakt 70 Jahre Verfassungsgerichtshof NRW" (ceremony 70 years of the Constitutional Court of North Rhine-Westphalia), Dr. Dirk Gilberg shows how he visualizes the 16 articles of the Deutsches Grundgesetz as a photo artist. He correctly chose HA Schult as the protagonist for Article 5. Article 5 of the Grundgesetz protects freedom and from the beginning of HA Schult's artistic career this is one of his main themes.

War

On 28 October 1994, HA Schult staged an action dedicated to peace on Schlossplatz in St. Petersburg. In the city, which had been besieged and starved for years during the Second World War, point two tanks ripped apart the words "The War". The letters, between six and eight metres high, were strung together with illuminated chains.

The war machine hired by the Russian army was painted in white, the other in black, according to the principle of good and evil. HA Schult: "By tearing apart the German word DER KRIEG on historical Russian soil, a call is made worldwide, in the language of art, for new thinking in economics, culture and politics."

Art / Art Calendar / Environment, 1 November 2022

Artist Talk - HA Schul and Christa Steinle - We can influence people's thoughts, but not their actions. HA Schult at the Circular Valley in Wuppertal on 18 November 2022. Alethea Magazine has the honour to reproduce an Artist Talk that HA Schult had with the Austrian art historian and then director of the Graz Joanneum Museum, Dr. Christa Steinle on 7 October 2006 at Palais Herberstein.

HA Schult - Haus der Geschichte der BundesrepublikDeutschland ©HA Schult

Düsseldorf, 1 November 2022: The German artist HA Schult is a visionary and creates art of the great moment. For him, the epoch in which humanity lives is the rubbish time and this determines his entire oeuvre. Over 33 years ago, he recognised the role art must play in solving environmental problems and created an army of 2000 sculptures out of rubbish, known worldwide as Trash People. 1996 marked the birth of the Trash People in the Roman amphitheatre of Xanten and 1999 marked the beginning of their 26-year wanderings around the world. They always appear at very specific places in the world, like in 1999 at La Défense, Paris and in the same year at the Red Square, Moscow, in 2001 at the Great Wall of China, in 2002 in front of the Giza Pyramids in Cairo, in 2007 at the Plaza Real, Barcelona, in 2011 at Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen; the whole itinerary can be found below. Paris - Moscow - Beijing, was the prelude to the biggest art action of our time so far.

The army is still on the road, a last big appearance was in Sassi di Matera on 24 and 25 August 2019, in the presence of former German President Christian Wulff, before Corona made some actions more difficult.

Now the Trash People are on the road again. A current opportunity to meet HA Schult together with his Trash People is on 18 November 2022 in Wuppertal at the Circular Valley Forum meeting. (circular-valley.org)

In the following, Alethea Magazine has the honour of reproducing an artist talk that HA Schult had with the Austrian art historian and then director of the Joanneum Museum in Graz, Dr. Christa Steinle, on 7 October 2006 at Palais Herberstein. The occasion was the artist's participation in the exhibition SLUM curated by Peter Weibel in the Neue Galerie Graz at the Landesmuseum Joanneum.

His actions have always been sensational: in 1976 HA Schult filled Venice's St Mark's Square, which he called the Salon of Europe, with a flood of paper waste. In 1977, as a contribution to Documenta 6, he first flew an aeroplane covered with symbols of consumption over the New York skyline, only to have it crash. In the interview, we also learn background information about the Trash People.

Itinerary of the Trash people:

1999: La Défense, Paris

1999: Red Square , Moscow

2001: Great Wall of China

2002: Giza Pyramids, Cairo

2002: Stellisee, Zermatt

2003: Gorleben

2004: Grand Place, Brussels

2005: Palais Herberstein

2006: Cathedral, Cologne

2006: Piazza del Popolo, Rome

2007: Plaza Real, Barcelona

2007: Longyearbyen, Svalbard

2011: Telgte

2011: Mochental Castle

2013: Poble del Mar, Barcelona

2013: Recycling Hill, Ariel Sharon Park, Tel Aviv

2014: Clairefontaine People, Luxembourg

2015: Tollwood People, Munich

2016: AQ Andreas Quartier, Düsseldorf

2016: Prussia Goes Europe, Berlin

2017: Werderscher Markt, Berlin

2018: Convent of Saint Agostino, Matera

2022: Circular Valley, Wuppertal

About the interview:

The artist talk was held in German. Free translation by Alethea Magazine.

Christa Steinle: Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Our contribution to the Long Night of Museums is the presentation of the artist HA Schult, to whom we owe this installation in the courtyard, and at the same time we are already sitting here in front of a work from the collection of the Neue Galerie, namely Giza, Cairo from 2002, and I would like to start by thanking the artist of this work, 1000 Garbage Men, Trash People, Slum People, in front of the pyramids in Egypt. I would say that we will start with these rubbish men before we look back at the long artistic career of HA Schult, who had a very classical education at the Düsseldorf Academy, but who moved away from this education to a great extent, just as sculpture and painting changed very much in the course of or at the beginning of the 20th century. New forms of art emerged, action art, installation art - and these are already concepts that this artist is close to. I think action art definitely is, and you have been travelling the world with these rubbish men for 10 years now. It's always very specific places where we find these trash people, whether it's in front of the pyramids in Cairo, whether it's the Great Wall of China, soon the Piazza del Popolo in Rome, but they were also in Moscow's Red Square; they're very famous places and you reach a big audience through them and you're in the media. Do you think this is the new form of art, that you reach the biggest audience by breaking away from the institutions and going into the public?

HA Schult: No, it's not a new art that I'm moving into, there is no new art. Since the Ice Age it's always been the same: man rears up to draw attention to himself, life flows through him, and just as people danced in the Ice Age in the caves of Altamira in front of the first petroglyphs, so they dance today in New York, in the underground cars or in front of the surfaces of the underground cars. They have often shouted out their message, from the ghettos into the other parts of the city, with the help of art. Art is a vehicle on which we can fortunately live, and everyone can find their place in this vehicle. That's just as great for the painters who paint like devils as it is for the sculptors, and it's the same for the action artists. We all have room on this raft of art, don't we?

Christa Steinle: The space is there, yes. One of them takes up more space, just like her installation, and thus attracts more echo, more resonance from the public and also from the media. It is very difficult to paint so spectacularly.

HA Schult: Well, the Ice Age painting - of course, there was no Green Party back then, and there was no SPÖ or the predecessors of the government with you, but there was only art, and there wasn't even the Kleine Zeitung. Or the Observer. And to that extent, these artists could live without the media. We are the medium that carries the message.

Christa Steinle: In any case, but your art not only excites the media, you also want to convey a message with it. They are not just sculptures as such, as one can of course understand them. You help to decide the process of creating these so-called rubbish men, you determine their formal aesthetic solutions, for example, that they should only consist of Coke cans. All your art seems to me to have arisen out of an ecological consciousness, long before the Green Movement existed. I'm only thinking of your first big action in 1969, when you piled up 5 tonnes of waste paper in the Schackstraße in Munich and practically blocked the street. Is that analogous to the action of Joseph Beuys, who swept up the rubbish after a student demonstration and then brought it to René Block's gallery in Berlin, along with a golden broom, or Christo's barricade of oil barrels - your art can be seen in this context, can't it?

HA Schult:

That's right, but I would call Peter Weibel instead of Beuys. Beuys was still making drawings at the time and was an assistant to Mataré, and he worked on the eastern front of Cologne Cathedral, which is not exactly what I call environmental art. That was at the same time that Peter Weibel was walking on all fours past St. Stephen's Cathedral on Valie Export's leash. That was about the time when I filled up a street with rubbish and when a completely different artist, who unfortunately then kitsched himself up so much, entered the orbit of the media on the subject of the environment, namely her compatriot Hundertwasser. With the Verschimmelungsmanifest (Mould Manifesto), he spoke very strongly about the environment, while Joseph Beuys was still painting or drawing at the time. It was only in 1972, a long time, three years later - they do count in art - that Beuys got on the Green Party bandwagon, which made it quite popular, and he certainly had a very ecological past - you have to give him that - he worked in the fields with the Van der Grinten family, but I don't know if harvesting cabbage has anything to do with environmental art. Weibel was much further ahead.

Christa Steinle: So you were familiar with Hundertwasser's mould manifesto?

HA Schult: Oh yes, Hundertwasser was also very familiar to me.

Christa Steinle: Mould was also a theme of your action in Leverkusen, in Schloss Morsbroich, where you demonstrated slime algae and microorganisms, bacteria, in test tubes and transformed the whole museum into a biochemical precinct.

HA Schult: Yes, Hundertwasser had a lot to do with mould back then, and so did another artist, namely Diter Roth. He made bananas mouldy, for example, to make us understand that it is also a process when a banana goes mouldy, and at the time I was preparing an exhibition in Leverkusen, the chemical city of Germany at the time. I wanted to demonstrate the war of the microbes. Namely, I tried to make visible what surrounds us every day. This happened in the following way: I exposed the air in Leverkusen to a nutrient substance, on 100 Ytong plinths, and this nutrient substance absorbed the air and changed colour as a result.

In practice, I exhibited the air of Leverkusen in Leverkusen. I filled one room with nine hundredweight of mashed potatoes, which was very expensive for the city. Another room was covered with French fries, because of the structure. And one room of the museum - a similar building to this one, by the way, not quite as beautiful and not with such a past, the dance hall, it was filled with blue-green algae. I covered the floor with foil, filled it knee-high with water, and set blue-green algae in this water. Blue-green algae are phototactically sensitive, they crawled towards the only light source I had in the room and were then pushed away by the more vibrant algae. At the peak of their life they were cobalt blue, only to disappear back into oblivion by the more vivid ones.

I tried to show life and death in the museum in a kind of time-lapse system, and perhaps I did it in a very sensual way. Then a visitor pricked the foil and all this broth ran into the ceiling, and for months afterwards you could still see the remains of my exhibition in the stalls, the exhibition could not be killed, although it depicted life and death - of course there was a city council meeting, the museum director was violently attacked ...

Christa Steinle: You called this exhibition "Biokinetic Situations" at the time, were you familiar with the French Situationists?

HA Schult: Oh yes, also the Russian Situationists. Because what I'm doing, if we now return to action art, also builds on the art of the 1920s in Russia or on that of the Futurists in Italy. Tatlin and all the others went out into the streets with public sculptures, they wanted to escape from the enclosure of conventional ideas of art, went out into the streets, and were then abused by politicians of all kinds, Lenin, Stalin, and later the Duce and Adolf Hitler. But the confrontation with the scissors in the head, which we found in Germany and elsewhere after the Second World War, only took place in the 1950s and 1960s, and here the keyword Christo is very important, who barricaded a street in Paris with oil drums, that was precisely at that time.

Christa Steinle: What do you say to your artist colleagues, Günter Saree, Ulrich Herzog, Jürgen Claus? They cooperated with you?

HA Schult: Yes, Günter Saree was a constructivist artist who painted neat pictures and then came across me, got a bit confused by it and was involved in the Schackstraße action. He had not yet found himself at that time, he then later left behind a very consistent early work, with some very beautiful actions; unfortunately he died very early. Jürgen Claus is still alive, he wanted to do underwater art and became a professor, something proper. And Ulrich Herzog, he opened a taxi company. He was only there for a short time; not to be confused with Werner Herzog, who still lives in Germany and makes films and is very well known from that time.

Christa Steinle: You were then always apostrophised as a biokineticist, or was that a creation, a neologism that you chose for yourself as a job title, which indicates that you go beyond the field of art into other processes, into life processes.

HA Schult: Yes, the 1950s were very productive in Germany, just as they were in Austria, there was that deserving Monsignor Mauer in the Galerie nächst St. Stephan in Vienna, there was Alfred Schmela in Düsseldorf here in Germany. At that time in Düsseldorf, after the war, we saw the first expressions of artists who went out into the surrounding area, into everyday life, there was the painter George Mathieu, who painted like a madman in shop windows, in Paris and also in Düsseldorf, there was that admirable artist Yves Klein, who also died very young, then there was Lucio Fontana, who destroyed the canvas, and all that left its mark on me.

At the art academy, which they very honourably concede to me, I learned that I can also paint a bunny and a turtle, or even a nude, if it comes down to it, at this art academy in Düsseldorf, from which Paul Klee was chased out in the 1930s, and where one first had to find oneself again after the war with few reasonable professors. RheinRuhrCity was a melting pot, also because of the money that gathered there for artists from France, from Belgium, also from the USA; many careers, e.g. those of Andy Warhol or of Bob Rauschenberg, they all began in RheinRuhrCity, in the huge landscape from Dortmund via Krefeld, Leverkusen to Bonn, where one of the largest cultural event carpets after the Second World War in Europe was created.

Christa Steinle: You mentioned Yves Klein, couldn't one see a certain parallelism, this obsession for the car, which you also developed to a certain extent in your action, in which you crossed Germany, tens of thousands of kilometres. Yves Klein also drove through the countryside with the canvas on his car, and the traces that the air and the water left on the canvas were the approved work of art.

HA Schult: Yes, it's good that you say that, because it completely slipped my mind. I notice it in retrospect - it's not in my book, but it strikes me now, just as it only struck me as an artist after I had made these 1,000 sculptures, what they have to do with the terracotta army in Xiang. We artists often do things where we don't even know what we're drawing from. We just have to admit it - and I've already tried to admit this with the talk of the Ice Age, which has influenced many artists - because we are all standing on the ground of the past and drawing from all that. Right: Yves Klein did this action, which I also remember now, I drove 20,000 kilometres for 20 days, that was in 1970, years after Yves Klein, and I had the windscreen changed every day because they were the evidence of the journey - it's the original dirt of the 60s, every insect immortalised on it, that's authentic.

But what mattered to me was the process: Yves Klein was still a traditional artist in the very best sense of the word, who gave us such a large imaginative frame that I was admittedly able to move within it. But of course Yves Klein was still striving for the completed picture.

He was a master at completing that by just setting a final chord with his blue paintings. That was not my thing. My thing was the process, the procedure, the madness of the motorway, the surrender on the motorway, namely that we no longer live in the Stone Age, but in the congestion age; and so we also no longer live only in the congestion age, but we also live in the rubbish age. On that planet Earth that we are collectively in the process of filling up, although it was only given to us on loan. That became my theme, and of course there are artists on whom I build, above all Arman, who worked with rubbish or leftovers very early on, then of course my friend Bob Rauschenberg, who at that time, in 1958, exhibited for the first time in Europe in Düsseldorf, and who had a very strong influence on me, which I also always told him. To reproduce this art form of the decomposing process, of the madness in which we live, that's what I wanted to do.

And if today you see models walking down the catwalk in Africa with rubbish underneath them, in 1969 in Schloss Morsbroich they were walking over mashed potatoes or over microorganisms. About the war of the microbes, as a critic once called it. All this has accompanied me until today, of course with a different breath, because what I do is very elaborate, there are 1000 sculptures that I have made. I have made 2000, 1000 I sell to finance the trip, and 1000 are the travellers. When one has travelled and is sold, another one moves up. At home, a Trash Man like that is very pleasant, it doesn't contradict, it's ideal for single households, and you don't feel so alone, and there's always someone there with whom you can't exchange a word or two, but whom you can talk to.

Christa Steinle: Let's move on to documenta 5, 1972, which also caused a great stir because of its action with the soldiers. Can you perhaps explain that a little?

HA Schult: At that time I was a young aspiring artist, and I had an idea for the documenta, which was made by Harald Szeemann, that legendary man who removed himself from the museum scene into a curatorial career. For Harald Szeemann, documenta 5 was a breakthrough and proof that you don't necessarily have to be in the service of a house to convey art, but that you can also work as a freelancer. Today there are many such curators; he was, you could say, the first to set an example with documenta 5. He was a very liberal man, was actually a trained window dresser, which always goes under the radar, but why not. And he lived in a rather narrow radius, but trilingual, in Bern. That's where he had the art museum wrapped for the first time, by my colleague Christo. And then he did the documenta, very elitist on the one hand, completely with his signature, and I was invited, which was very important for me, because - even though I'm quite well-known today - you have to exhibit in museums so that ordinary people believe that this is art.

So I took part in the documenta twice, and my works also hang - if I may say so - in almost 60 museums around the world. At that time, Harald Szeemann invited me to participate in the documenta with a serious contribution, and I then exhibited, very unseriously, a live soldier guarding empty Coca Cola bottles. There was a point to that. Because every war since the Second World War begins with Coca Cola. First Coca Cola was in Vietnam or Korea. Today it is also McDonald's. Also in Beirut and in Afghanistan, that's logical, the Americans are so used to this drug burger, it naturally has to accompany the war, and Coca Cola too.

So I deliberately showed Coca Cola bottles there - then something very crazy resulted, which also concerns the archaeology of the present, my colleagues from the USA kept stealing the bottles. Because it was such a classic. They didn't make bottles like that in America any more, they were these humped bottles where the lettering was still moulded in. The mountain of Coca Cola bottles became smaller and smaller, the most famous artists had the audacity to reach into the bottles, as an archaeological find of the present. I've experienced that here too, with my sculptures in the courtyard, where someone from Red Bull was walking around confused because there's no Red Bull can in between. It has to be said that when I started making the sculptures, there was no Red Bull in Germany. The inventor has made a world career within ten years, and that is precisely a parable for the archaeology of the present, because today's crushed Red Bull can is tomorrow's Roman shard.

In one of the pictures shown in this exhibition, you can see a hole near Cairo, about 10 kilometres as the crow flies from the pyramids of Giza, and in this hole lies the rubbish. The hole is maybe 800 metres or a kilometre in diameter. The Egyptians have dug a deep pit and that's where they throw the rubbish in. The rubbish has already been evaluated by the poorer people beforehand, in front of their houses, and they have taken it home with them. When you visit the people there, the flats are often full of rubbish. The rubbish grows up to the roof of the house, because the family evaluates it, and then throws the rest back outside the door, then the even poorer people come and take this rubbish again. In the end, the rubbish ends up in a huge hole, and people live in this hole who live off the rubbish that is thrown there, and who then evaluate it in turn. There are hundreds of dogs around it, and they fight over the last bits of rubbish. You stand up there and look down at the flames, because there are often fires caused by the sun. After three years this hole will be filled with sand and two years later there will be a Holiday Inn or a golf course. It's a cycle, for us it's unimaginable how they handle this waste there.

While we build the most expensive, elaborate waste incineration plants here, they do it the easy way, similar to the Russians, who throw the burnt-out nuclear fuel rods into the front gardens of the Western world. That is also a side effect of this action, to show how people in China or Russia, in Switzerland or Austria, in Germany or in Egypt deal with this subject in very different ways. That's my idea of a global sculpture that I use to show the way people deal with a subject that will have a decisive impact on all of us in the coming decades, namely the subject of rubbish.

Christa Steinle: So it's a critique of civilisation. That's certainly what it was when you covered St Mark's Square with tons of paper. That went through all the media, on the front page, it was covered several times ...

HA Schult: Yes, that was a cool action. That was in 1976, when I was already quite well-known and also disreputable, but I was already hanging in numerous museums with my picture boxes, so it was already honourable. But now I was standing on St Mark's Square at night, which is a symbol of time standing still. Everyone who has stood there, whether from Australia or China, from Germany, Austria or wherever, takes the still image of St Mark's Square home with them. It is the salon of Europe, one of the most beautiful, if not the most beautiful square in the world.

And I thought that if I threw into this square what we had spewed out, what we had vomited out, what we had caused, I could perhaps present the topic of the environment a little more clearly than the one or other UNESCO congress. And I have succeeded in doing so. For I tipped the present into a container of the past, and the future so near, 1976, and that met with reactions in the Vatican newspaper as well as in the Bild newspaper, in the Kronen Zeitung as well as in Prawda. That was, as you quite rightly mentioned at the beginning of this conversation, of course a media sculpture: they are images that appeal to people in the media in such a way that they keep them in their minds. And that's the good thing about this art, that it also takes place in the heads of those people who normally haven't moved to the museums, for whatever reason. I also draw people into the museum who normally don't find their way in. And that is a dialogue that I am proud of in a certain way, and that I share with liberal museum directors.

Christa Steinle: But beyond that, you must be a master of logistics - normally art in public space has a very hard time getting situated, especially it's hard to get all the permits in the first place. Just when we want to start a smaller action, it's often more than a hassle.

HA Schult:

When I wanted to go on the Wall for the first time in China, it took me months, actually years, to get such a permit. To stand on Red Square, a few years after Perestroika, with 1000 sculptures, to stand on the Great Wall of China, in a country where modern art was frowned upon for decades, for centuries, to stand in Egypt, which has been hit by terrorism again and again, these are long processes. Of course, and that's the beauty of this art, you have to talk to everyone from the car park attendant and the customs official to the president of the country. And that is also what makes this art dynamic, namely that it works across normal social barriers, but of course only if the theme works, that is very important, and my theme, it is clear in every country, is the core theme of our epoch.

Christa Steinle: I imagine it must have been particularly difficult on Red Square. How were you able to convince Putin there?

HA Schult: Well, I didn't have permission on Red Square, and I didn't have permission in China either. I would like to use these two examples to tell you how difficult it is. In 1994, I worked in St. Petersburg and placed two tanks on the square where a revolution broke out in 1917 that still concerns us today, namely the October Revolution. And on this square, in a city that Hitler deprived of a million people in the Second World War, that he starved to death with his eternal blockade, I wanted to tear up the writing "Der Krieg" (The War) as a German artist.

In order to get this permission, I got through the mayor at the time to a second mayor, I don't want to take this too far now, but take it as an example of how you have to have such a worldwide network. And that's how it was in St. Petersburg at the time, when Mr Sobchak sent me to be his deputy. He was a stocky man, no taller than me, he had eyes like a lizard, was very athletically built and spoke fluent German with a little Saxon touch because he had been a KGB employee in East Germany to carry out economic espionage there. And I developed a friendship with him, I couldn't help it, otherwise I wouldn't have been able to do it, and he told me about his past. In Russia, you could only get to the top via the KGB, whereas in New York, let's say, you could box or sing soul to get to the top from the lower class, or deal in drugs, none of that was possible in Russia. In Russia, you just went to the KGB. And so a friendship developed, I got permission, I paid 60,000 dollars for it, so that disabled people in St. Petersburg could roll down Nevsky Prospekt and no longer had to rely on the stairs; that was my foundation to get permission to tear up "War" on Palace Square. These handicapped stairs have not been built to this day, but I have paid for them before. And then later I was busy in Moscow getting to Red Square, that was in '99. The Ministry of Tourism showed me around the city. We passed the KGB and I asked one of my companions who was in charge and he gave me a name. I immediately called Germany and said, "Call this man and see if his mobile phone number still works, because I knew him from St. Petersburg. And it still worked.

Elke called and told him, HA needs you, come to his hotel. And there he came to my hotel and the street was closed, there were drivers with Kalashnikovs, and in the hotel lobby everything was shut down - there was just a film festival, Alain Delon, the famous French actor, had to stay in the lift for an hour and a half for security reasons - and we had lunch together. I asked him if I still needed a permit, because I had got to know him so well in '96, and he said: You don't. And so I never had a permit and I didn't have a permit.

And so I never had a permit and just put the Trash People in Red Square. But all the important people knew that he had been to lunch with me. He then became head of state six months later. That's how you can realise a project, of course; if you bet on the wrong person, it works less. In 1986, I had an appointment with Deng Xiao Ping to build a mountain out of European soil in China. I wanted to put a mountain in the Forbidden City and bring earth from all the countries of Europe to build a mountain. The Chinese were to pass through the mountain, which meant that I wanted to send them through Europe, so to speak.

And he listened to that, very briefly, I had 20 minutes, of which they chased me through the corridors for 15 minutes, then five minutes remained for the conversation - and after that my visa was revoked. He had told me during this visit: That doesn't happen here. You go in as Chinese and come out as European.

And that's how you can go wrong. Then, in 2001, the sculptures were on the Great Wall of China, because the Chinese wanted to hold the Olympics in 2008, and they used me to testify to their new liberality, and I was happy to be used to push this project through. It is always a window, a political window, a social window, sometimes it is quickly closed again, as for example with the action The War, because shortly afterwards the Russians went on campaign in Chechnya, and that was the end of peace.

Christa Steinle: From Red Square back to New York - that was an action you chose for documenta 6 with New York as its setting, a work entitled Crash, in which you crashed a plane near the Statue of Liberty - an almost prophetic work, one could say in view of 11 September. This was simultaneously transmitted to the documenta via satellite. You called this action A Monument of Our Time, similar to the name Tinguely gave to the self-destructive machine in the garden of the MoMA in 1960. When I think of the photos of this action - the plane between the Twin Towers ...

At that time you already spoke of the media sculpture, why did you call it that? Because of this transfer to the documenta?

HA Schult: In 1977 I moved to New York and was invited to contribute to documenta 6. I had the idea of questioning the dream of flying, which has been dreamed of by artists since Leonardo. To justify myself, there was no such thing as hijacking at the time - it hadn't even happened in 1977 - and so I came up with the idea of flying a plane tattooed with the insignia of consumption, Coca Cola and Marilyn Monroe in this case, and an American flag around the Alps of Capital, the skyscrapers of New York. The World Trade Center was a few years old, and this plane circled the World Trade Center, flew over to the Statue of Liberty, and then crashed into the biggest dump in the world at the time, Staten Island. Staten Island is not like other countries, like Egypt, where a hole is dug, or like Germany, where a mountain is created, but this is a land reclamation project. With Staten Island, land has been reclaimed through rubbish, it's a huge rubbish landscape, or it was then, now there are houses on it, but it's still a rubbish landscape.

That's when I wanted to crash the plane and I fixed it with the pilot, who was a very professional pilot. He was shot down twice as an army man and didn't get more than a medal for it. He got $60,000 from me to actually do this crash. I bought a Cessna, flew that Cessna over Manhattan and then crashed it into the dump. The crash is the sculpture, a sculpture built to thousandths of a second, photographed by the same photographer, now we come back to Yves Klein, who photographed the famous window jump by Yves Klein, who was supposed to fool us into thinking that as an artist you could also fly: Harry Shunk. And this impact was photographed, the pilot survived it, he was able to do something like that; we also underpinned the point of impact below.

We didn't have computer calculations or mobile phones back then, everything was completely different. This satellite connection was very complex; it was the first ever satellite transmission of an art action, because at the same time as I was doing it, the action could be seen in Kassel at the documenta on the Hercules, a monument of a different era. And it was called Crash, a monument to the United States, and I added this plane to the rubbish. The macabre thing is that on 09/11 the rubbish from the World Trade Center was taken to Staten Island by the CIA and FBI and the remains of the World Trade Center are on my plane today. That's one thing no artist can do. But with the panic that exists in America about immigration, I always make sure that these photos don't appear, otherwise people will get the wrong idea. My action is a parable for the fact that we artists have to keep our finger on the pulse of time in order to show people something that concerns them all.

Christa Steinle: In 1985 there was another action in New York when you posted the Brandenburg Gate in front of the towers of the World Trade Center, a replica, so to speak. Here, too, there was a satellite television transmission of the New York Wall onto the Berlin Wall. Was that a kind of double critique or consumer critique of New York, as towers of capital, as Beuys then also called them, Cosmos and Damian, and of the wall of Communist ideology?